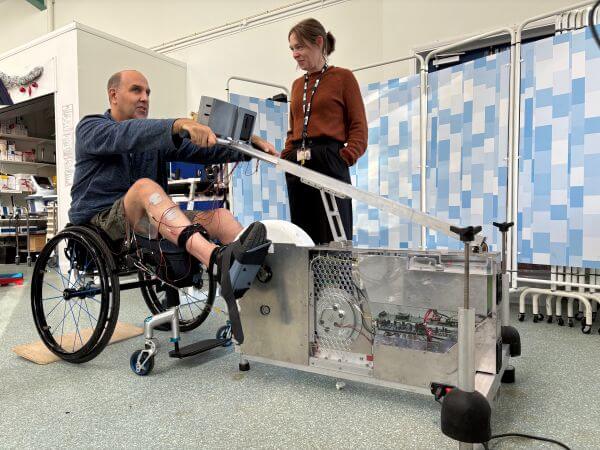

The RFU Injured Players Foundation (IPF) is funding a trial with University College London (UCL) to understand more about how FES (functional electrical stimulation)* cycling can help people who have sustained a spinal cord injury regain movement, balance and mobility in their lower limbs.

Working with an exceptional and highly experienced team, the trial builds on previous findings that have shown that this exercise increases an individual’s strength and cardiovascular function, but also sometimes reduces paralysis. The method requires a cycling machine, which is called iCycle, that stimulates the leg muscles and has a motor to establish cycling motion while motivating the user with virtual reality. This particular trial focuses on spinal cord injured people who are marginal walkers, and also in understanding the biomechanics and neural control of the exercise.

Speaking to the protagonist, Professor Nick Donaldson, the idea and thought process has been on his mind for a number of years: “It was back in 1978 when my professor told me to produce a nerve stimulator that would help people with spinal cord injuries walk. The idea of FES-cycling initially came about in the late nineties when I was visited by a GP called Roger Fitzwater who had been in the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital as a spinal cord-injured patient. In his job, he had been encouraging his patients to take more exercise for their health and he came to me and said that FES walking was a waste of time.

“He encouraged me to concentrate on getting people cycling as it’s a much easier thing to implement, because exercising the large muscles of the legs is essential for fitness and general health.”Nick and his colleagues proceeded to set up Roger with a mobile recumbent tricycle adapted with FES and he started using it on a regular basis. A little over a year later the team was amazed to find that Roger had regained voluntary control over one knee, which had been completely paralysed. At that time, this was a complete surprise, to see the extent that recovery was possible. The question that therefore needed to be answered was whether the recovery was caused by the combination of voluntary drive to the muscles in the leg, Roger trying to push the pedals, and the simultaneous electrical stimulation.

This discovery propelled Nick to consider the development of an indoor machine with Virtual Reality (VR), which was an idea on the horizon at this time. The VR would encourage patients to make an effort without the risks and difficulties of cycling on the road. That was the start of the development of iCycle in 2009. The current iCycle model is the Mark 3, which has been developed thanks to grants from the IPF and the Inspire Foundation. A key feature of all iCycles is that stimulation is applied on alternate revolutions so that the voluntary effort can be measured as the crankshaft torque, and on the non-stimulated revolutions, without interference by the stimulated muscle contractions.

The current iCycle incorporates what has been learnt from clinical trials of the earlier versions. It is a complex machine as it needs to include a number of functions to enable its use by different people with different levels of injury. Some of the core features include:

· Adjustability so that people with different types of wheelchairs can use it, including height and length of cranks

· Robust enough to be used by both strong people and people with heavy legs

· A transducer to measure the torque of the crank shaft.

· Ability to stimulate with the right phase so muscles are brought in at the appropriate phase in the revolution of the crankshaft to drive the pedals.

· Wireless technology to avoid trip hazards - there are 3 different wireless signals inside it sending the wireless video signal to the display.

· Safe and intuitive user interface.

· Microcontroller for low level control.

· High-end games computer to run Zwift VR.

· Designed to meet the standard for electrical safety.

· Motor and motor controller able to act as a brake and able to dissipate the power produced by the user.

The Principal Investigator for the project is now Lynsey Duffell who got involved in FES-cycling for her PhD.

“At the time Nick was running a multi-centre trial where they were giving people tricycles to use at home and he wanted them to train intensively for one year, five days a week for an hour to see what the health benefits would be. The participants were all completely paralysed, and we assumed that the muscle contractions were entirely due to the electrical stimulation. They all increased their muscle size and strength, and were able to propel the tricycles, at least on smooth level surfaces. It was real exercise, produced artificially. We encouraged them to participate in indoor cycling games. We did not expect neurological recovery, or reduced paralysis.

“With iCycle, we expect to see the same benefits from the exercise of muscles, but the important difference is that we are now looking for reduced paralysis, and reduced disability.”

The current trial has five participants with chronic injuries. They have all trained two or three sessions per week at the hospital. Every four weeks the individual is assessed and given an option to carry on or not, to a maximum 12 weeks of sessions. IPF Member, Steve Gascoigne is one of the current people on the trial and he is already seeing the benefits.

“For me this has come at quite a good time and been really, really good,” he said. “I had an incomplete spinal cord injury when I was playing rugby aged 17. This gave me Brown-Sequard syndrome where I have reduced motion on one side and reduced sensation on the other, so I had reasonable strength in one leg, with very significant weakness and movement in the other one. As with a lot of things if you’ve got an impairment in one limb you tend to overcompensate with the other one. I’d never been able to cycle before because I have such an imbalance between my two limbs.

“I actually had a fall and injured my knee just after I signed up for the trial, so that delayed everything for me. But ultimately this has proven to be quite good rehab for that injury – the regular motion and cycle sessions have not only helped with my fitness, but also helped the knee start to recover and feel a lot stronger.”

Steve also wants to highlight the other benefits that the use of the iCycle has offered him. “Having access to the right equipment shows there is more you can do than you realise. Keeping fit is key for anyone, but especially for those with a spinal cord injury. It’s really easy to become inactive, and our health challenges can be compounded by inactivity, so this has been great for me in that respect.

“Being able to make my legs active has also been key - the repetitive motion of the cycling has been good for my joints in terms of flexibility and I’m just much stronger and fitter as a result of the trial.”

With such wide-ranging positive results there is a question as to why this therapy isn’t used more readily for those with spinal cord injuries with Lynsey highlighting that accessibility and availability is the main challenge in this area.

Lynsey commented: “We’d like to see the iCycle become something that is more available for those with spinal cord injuries, so in hospitals, gyms, neuro-rehab settings and spinal injury units. However, there aren’t many of the latter in this country and they are mainly for inpatients, so there is a real lack of provision for outpatients.

“We’d love for them to be affordable so people could have them in their homes or accessible so GPs could prescribe say a three-month course using an iCycle to improve issues relating to CV fitness or general health where exercise would be a benefit.

“But it’s not cheap to get a bike on the market that has all the regulatory approvals. The current iCycle we’re using is a research machine and it would cost a huge amount of money to get approvals to make it commercially available. The FES bikes that do exist are very expensive so the best solution would be to try and drive costs down and make them accessible in gyms.”

For Lynsey therefore, the focus is on how they move this trial forward from its current standpoint, around which they are constantly having conversations. “We’re talking to a physio who works in a neuro rehab gym to see where we can go with it. Our biggest barrier on this project has been recruitment and getting people here to the hospital three times a week to do their training.

“So now we’re looking at getting a bigger group of subjects set up in a way that will be more convenient for more people, so getting several bikes across several gyms and getting people coming to do regular training with regular assessments. We’ve had a lot of interest so hopefully by delivering it in this way we’ll make it more accessible and can set up a study that allows us to build a good evidence base.”

The benefits are also wide-ranging for the IPF. Dr Karen Hood, IPF Director commented: “The direct practical benefit that this activity has on the individuals involved is clear for all to see. Our charity is very much focused on the individuals we work with and wanting to remove the barriers to their daily lives. So, if that means for Steve rehabbing from a knee injury it’s great that he can be involved in this sort of project.

“But for us it’s also linking into the ethos of the rugby family. Everyone we work with is sporty and has been used to the train harder for better results mentality and a lot of that can be taken away with an injury like this. So, to be able to give them that control and that power over their own abilities and exercise again is something that resonates a lot with the people we work with.

“It’s also about making a contribution to the broader communities, both research and spinal cord injury, which is something we’re hugely proud to do and anything that can be done in that space is just going to benefit everybody which is an absolutely fantastic thing to see.”

As a member, Steve has benefited from the support of the IPF and pays tribute to their holistic approach: “It’s never just the injured person for the IPF and this is what they’re really good at. It’s their family, their friends, their relationships; the injury affects all of that so anything that has a positive benefit, whether physical or psychological, is hugely beneficial.

“The psychological benefits of doing exercise are really worthwhile – it gives you motivation, a reason to go out and do things and that does play through in terms of how you feel about things generally. Even for me and I’m generally a very positive person, but the experience of having that fall and the uncertainty of what that meant for my mobility and independence going forward was really hard. It was possibly the hardest period I’ve been through in the entirety of my injury because I didn’t know if that fall was going to mean that was the last time I did certain things. This trial has proved it wasn’t and that has been hugely important psychologically for me as well as physically.”

For Nick it has been a labour of love for most of his professional life: “It’s really thrilling isn’t it, seeing the development of where we came from in the late nineties to 2025! It’s been a lot of my life and I’m very happy with that. It is a fantastic opportunity to do something that will directly help people with spinal cord injuries.”